Mendo Gulls, Part 5. Gull flocks, hybrids, and rarities

This is the fifth and last in a series of gull identification and ageing along the Mendocino coast. See the May, August, October, and November issues of the Oystercatcher for the other four series covering our regular species of gulls.

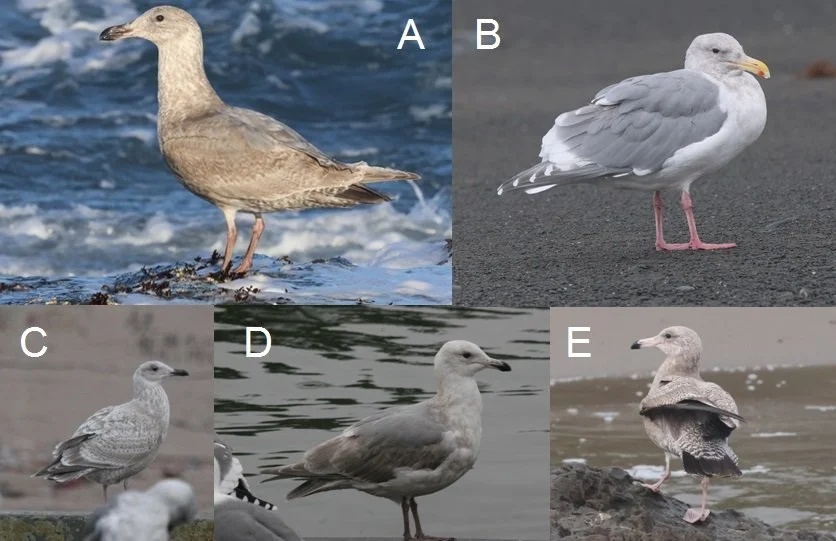

Figure 1. Finding Gulls.

Figure 1. Finding Gulls. I’m slowly figuring out the best ways to find and study gulls along our coast. Sometimes I like it when there are 50-100 gulls, as when there are more than this it can become overwhelming. But on other occasions I’m up for sifting through 1,000 or more. In winter, I’ve had the most luck during rainy weather at creek mouths. These include Wages Creek (top two images, 11 Nov 2025) and Virgin Creek (bottom left, 4 Nov 2025). Note the paler-backed American Herring Gull in the top-right photo, preening and with its tail up. But at other times, during nice winter weather, there can be ZERO gulls at these locations, or close to it. So put on your wellies and get out there in the rain or drizzle to look at gulls. What could be more fun than this?

Other creek and river mouths that can have big gull flocks in winter include Ten-mile, Pudding, Navarro, and Garcia, the last of these best for study if you can hike in from Stoneboro Road. On December 20th this year there were about 3,000 gulls wheeling around about the mouth of Abalobadiah Creek (north of Ten-mile). Luckily for me this beach is inaccessible so I didn’t have to do anything more than just enjoy the swirl.

Late April and early May can also be a good time to find interesting gulls, as was the case on 2 May 2025 at the Inglenook Creek Mouth (bottom right). At this time most Western and California Gulls are off breeding, leaving behind some oddball first-winter birds. From left to right here are American Herring, Glaucous-winged, American Herring, and Thayer’s Gulls. The Vega Gull shown below was also there at this time.

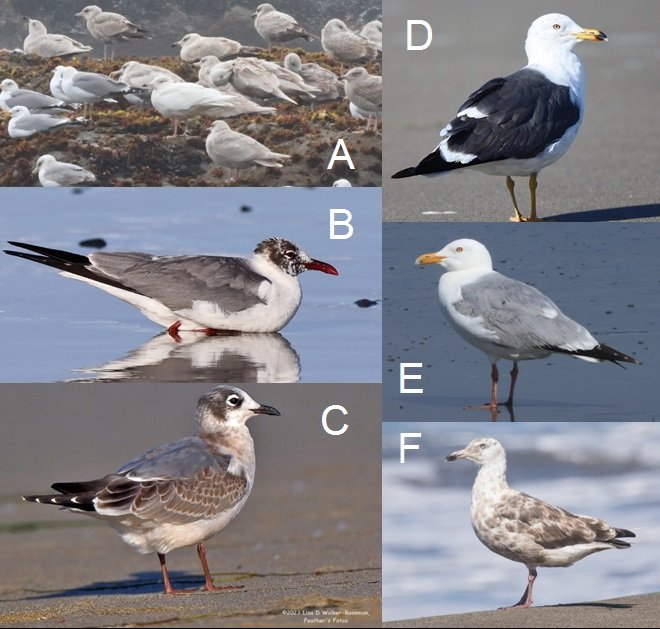

Figure 2. Hybrids!

Figure 2. Hybrids! I know, I know, it’s hard enough to pin the species down and so I won’t dwell on hybrids too much. As I’ve mentioned throughout this series, first do your best to learn our regular gull species. Once you feel comfortable with these in, say, 15-20 years (like me!), then you can start thinking about hybrids for the birds that just don’t seem to fit what you know. Basically they can come in all combinations of characters between parental species which makes things, um, challenging.

Our most common hybrid is Western (WEGU) x Glaucous-winged (GWGU), or “Olympic” gull (A-B). As you move up from the Columbia River through the Puget Sound and to Vancouver, these basically form an even cline between the dark-backed WEGUs we see here to what we think of as a GWGU. This cline also continues both south toward even blacker WEGUs breeding in Baja California and to whiter GWGUs breeding in Alaska. The way I look at it, dark back + dark wing tips = WEGU, pale back and pale wing tips = GWGU, and hybrids are usually (but not always) in between - medium back and medium wing tips. But sometimes they can show various other combinations of each species, especially regarding tail color. At top left (A, 22 Jan) is a first-cycle hybrid showing a medium pale back and pale wing tips. You might try to put this into the GWGU box but note the tail color, too dark for GWGU, and indicating a hybrid. The adult at top right (B, 11 Nov) is also a bit paler on the back and wing tips for a pure WEGU. Another clue to this being a hybrid is the dark mottling to the head as adult WEGUs have pure white heads. As far as ID’ing these, structure and bill color come in handy, as parental species as well as hybrids show the same characters including large size and bill in both of these examples, and the entirely black bill of the first-cycle and early second-cycle birds.

Another hybrid we get fairly regularly is American Herring (AHGU) x GWGU, or “Cook Inlet” Gull (named for where these species interbreed). These commonly can resemble AHGU but with paler wing tips, or they can resemble GWGU but with a thinner bill, which can be brighter pink with a dark tip in first and second-cycle birds (unlike the mostly or entirely black bill of GWGU at these ages). The first-cycle bird at bottom left (C, 6 Dec) is like a AHGU in plumage pattern but too pale and with a bill showing the color of GWGU but too thin, in the direction of AHGU. The second-cycle bird at center (D, 2 Jan) likewise resembles a paler version of AHGU, with wing and tail feathers in between GWGU and AHGU, and a bi-colored bill that is more like AHGU at this age though a little stouter than typical. Finally, another hybrid to keep in mind is AHGU x Glaucous Gull (GLGU), or “Nelson’s Gull,” shown at bottom right (E, 2 Jan). In this case the plumage is like first-cycle AHGU but this bird was huge and had a giant, bright pink based bill of GLGU at this age. I suspect this one may have been an F2 hybrid with 75% AHGU and 25% GLGU. Hybrid gulls seem perfectly fertile and frequently back-cross, adding to the fun! I hope this small lesson in hybrids can at least result in your admitting to their existence!

Figure 3. Rare Gulls

Figure 3. Rare Gulls. We’ve so far covered our eight common gull species and now for the fun part: looking for rarer species. Here are six from the Mendocino Coast. Speaking of GLGU, the pure white bird A (12 Mar, south of Virgin Creek mouth) is a second-cycle bird. The bright pink-based bill with sharp black tip helps identify this species and age from GWGU (which can bleach to being this white but has a mostly black bill at this age). Purely leucistic gulls are also a consideration, but these usually have entirely pale bills. GLGU is rare here in Nov-Apr.

This molting adult Laughing Gull (LAGU, B, 31 March) and first-cycle Franklin’s Gull (FRGU, C, 5 Oct) were both photographed by Lisa Walker at Virgin Creek mouth. These two species can be similar (they used to be in genus Larus, like the rest, but have been moved to genus Leucophaeus) but LAGU is typically larger, has less white in the primaries, and has smaller eye arcs at all ages than FRGU. The bills of both species are black in fall and winter and red in spring and summer, but note the much larger size and droopier shape of the LAGU bill. Both of these species can show up at any time of year, though FRGU is very rare in winter.

Lisa Walker also took this photo of a fourth-cycle Lesser Black-backed Gull (LBBG, D, 27 April) at Virgin Creek mouth. This species varies a lot and is most similar to WEGU in our area (the back color can be grayer than in this bird) but note the longer and thinner bill, longer wings, and, especially, the bright yellow legs of older birds. Younger LBBGs have pink legs so we rely more on long wings and bill shape to separate these from WEGU, among some other subtle plumage features. The lack of white to the wing tip and the black bill tip identify this as a fourth-cycle bird rather than an adult. LBBG can also show up at any time but is most frequent in fall and spring.

I found the bird in E on 2 May 2025 at Inglenook Creek mouth and have identified it as an adult Vega Gull (VEGU). This is a species from Russia that was split from American Herring Gull a couple of years ago, so we are still working on its ID. Adult VEGUs can be separated from AHGUs by being smaller in size, darker backed, with maroon rather than yellow orbital rings, and with duskier pink legs, all features shown by this bird (I estimated the back color to be between that of nearby adult CAGUs and WEGUs). The California Bird records Committee is currently reviewing a long-returning, wintering VEGU from San Mateo County which shows all the same features of this bird, so if that one passes muster with them, this one should as well! It would be a first Mendocino County record.

Another WEGU-like bird is shown in F (16 Sep, Ten-mile Beach, Roger Adamson) but why does the eye make it look like an AHGU? It’s because this is Slaty-backed Gull (SBAG), molting from first to second cycle; note the very bleached outer primary yet to be dropped. Besides the eye color, the stubbier look and darker pink legs are also features pointing to SBAG over WEGU. Separating first-cycle SBAGs from other species, however, has even the most expert of “Larifiles” putting their hand up! So don’t even try. This bird was the first record of an “over-summering” SBAG in California, all other records being from December-March, so congrats to Roger for a very significant find and great documentation.

Enjoy our beautiful beaches and coastline, made all the more pleasant when looking at gulls! I hope this series is of some help.